Blog

March 17, 2022

Telling the Holocaust through poems

Within the Museum’s collection of survivor testimony, there are countless stories of resilience, survival and great loss. It is difficult and at times impossible to put into plain words how unimaginable grief, suffering and trauma feels. As a result, many Holocaust survivors still find it difficult to describe their experiences, even today.

We share three poems from our collection of Holocaust poetry:

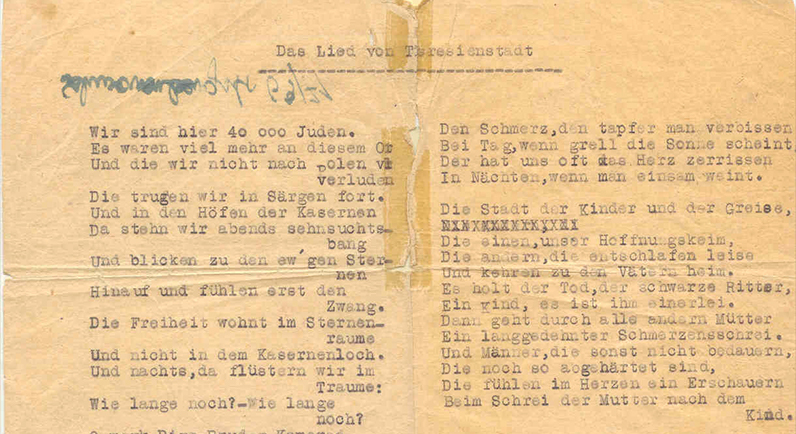

Song of Theresienstadt by Walter Lindenbaum, SJM Collection.

Song of Theresienstadt

In Song of Theresienstadt, the poet Walter Lindenbaum grapples with his longing for freedom from this dark place where he and others have been dehumanised, and reduced to a base, selfish version of himself. The poem was originally written by Lindenbaum in Theresienstadt, presumably in 1943-1944.

His incredible suffering is palpable. He writes:

Exposed does misery show itself

and every creature is blinded,

failing, in misery and stealing

self-preservation shows itself.

Both at the beginning and end of the poem, Lindenbaum wrestles with the fact that he remains in this “town of children and aged… the left-overs of the millions,” a place where countless others would pass through, only to meet their death.

Despite this, he ends his poem on a hopeful note:

And yet we kept the belief going

that at some time things will change

And it will one day become different

and if we get out of here

and become a free people on this earth

then I shall sing my song at home.

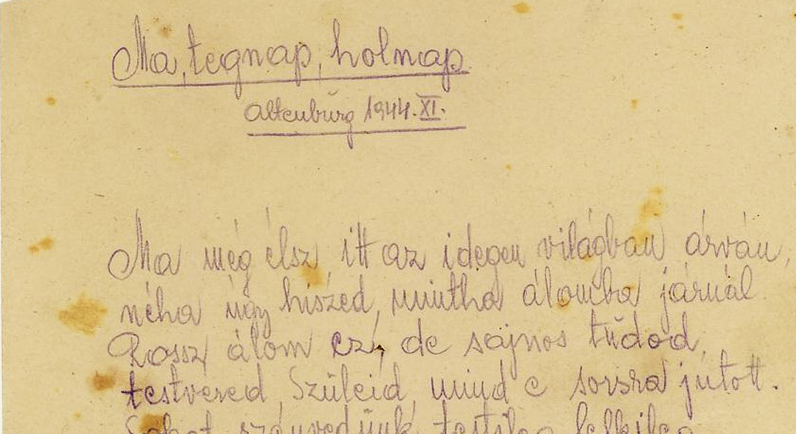

Today, Yesterday, Tomorrow, by Madga Bognar, SJM Collection.

Today, Yesterday, Tomorrow

Magda Bognar (nee Lowinger) was 23-years-old during her incarceration in Altenburg, a sub camp of Ravensbruck concentration camp, from November 1944 – January 1945. Little is known of Magda’s Holocaust experiences, as she never spoke of them during her lifetime.

Her three poems in our collection, entitled Ma, tegnap, holmap (Today, yesterday, tomorrow), Me is megtiidtuk (We too found out) and Dream, are the only testimony of her experiences, her physical and emotional suffering, and a record of the daily harsh realities she endured.

In each of the poems, Magda chronicles the daily realities of her physical suffering. She writes about

The intern camp dreadful to recall

eight hundred in one place, to sleep on cement

to queue for one bit of bread, a little warm food

terrible struggle for terrible survival….

Our hair shorn, brutally disfigured

waited for our fate in a single silk shred

and the march began, in a horrible procession

we could hardly drag our worn out bodies in the terrible heat…

famished all day you were wallowing in dust….

Magda’s resilience can be seen in the powerful use of her imagination. This became a way for her to remember a better past and hope for a better future. Just as in Lindenbaum’s Song of Theresienstadt, Magda’s poems end with a glimmer of hope.

Dream ends with:

Mama, I know that you are not with me

and yet I feel you here, your hands holding me

and as snowflakes are chased by the storm, so does my imagination fly away with you…

Whatever will happen I do not care anymore

because I believe that the dream will come true soon.

We too found out ends with:

Our dreams must come true one of these days

and when that happens we shall all go home

and we shall re-build our tiny nest all over again

where nobody ever can harm us again

and if they ask

are we happy, is it good to live like this

we shall say yes, because we learnt to suffer and to persevere.

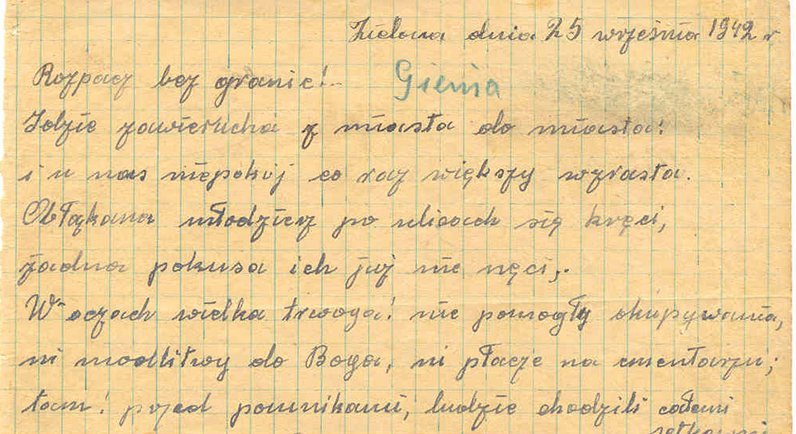

The fate of the poor ever wandering Jew, by Genia Kochan, SJM Collection.

The fate of the poor ever wandering Jew

Genia Kochan utilised poetry to mull over her decision to flee her home and the loss of her parents. Her emotive poem, dated 25 September 1942, was written whilst Genia was in hiding with her brothers and sisters in the city of Dzialoszyce, Poland, with a non-Jewish family by the name of Novak. Genia was one of seven children, who lived in Wadowice in southern Poland near the Czech border.

In 1939 the Germans bombed her city and the family decided to leave and go to Dzialoszyce, 150 kilometres away. After some time they returned home, but in a later Aktion her parents were shot by Polish policemen when trying to hide, while Genia and her siblings escaped back to Dzialoszyce.

Through her poetry, Genia conveys the escalating persecution of Jews and the dread that preceded it:

Despair without borders

A storm is moving from city to city!

And our fears progressively grow larger.

She struggles with the pointlessness of inaction and action. On the one hand, it is pointless to Genia to wait in fear:

Neither bribery, prayers to God nor cries in the cemetery helped

There in front of tombstones, hundreds of people came daily;

Children, the elderly, the youth, all today are as one with God

They beg to be rescued, for survival, they admit all their sins and give an oath to make amends

Today she uttered from the depth of her heart terrible groans, God!

Ease our torment.

On the other hand, she expresses regret for escaping:

I ran away but I myself I don’t know why? But I was terribly afraid of death; did I pity my own life? Did I pity the distress of my beloved?

I don’t know, I can’t say why

I only know one thing; that I am suffering terribly as a result of what had happened and that my heart whilst I am alive will not have any room for greater suffering

There will only remain a bleeding wound; it will never heal.

In her grief, Genia expresses anger towards her parents for leaving her, but it is clear that anger is also directed inwards at herself.

Her poem ends with a sense of despair and we see that in hiding her world becomes bleak:

Everything in the world is pale! Only in painful hearts it is blue.

Shortly before it was written, 10,000 Jews from Dzialoszyce were rounded up and deported to death camps. Terrified of discovery and of putting the Novak family at risk, the Kochan siblings made plans to leave. Though the details are unknown, Genia was captured and deported to Auschwitz where she was murdered.

Her poem was kept by the Novak family and returned to Genia’s brother Morrie after the war.

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.