Blog

January 18, 2023

History beyond the university classroom

By Dr Breann Fallon, Manager of Student Learning and Research

Since 2018 the Sydney Jewish Museum has collaborated with Professor Michael McDonnell from the University of Sydney in delivering his groundbreaking unit of study, History Beyond the Classroom.

During this unit, students visit numerous public historical and cultural institutions before committing to volunteering at an organisation of their choice. As a partner organisation for a number of years, we have seen many remarkable student volunteers working with various departments on projects with varying topics: from the Museum’s architecture to a collection of children’s plays to stationery sustainability rankings. Last year was no different as we hosted numerous enthusiastic and committed students in both the Education and Curatorial Departments.

Two of these students reflected on their time working with us and have shared the insights gained from their time at the Sydney Jewish Museum:

Darcy Owen, volunteered with the SJM Education Department

I knew it was going to be interesting doing my cataloguing project at the Sydney Jewish Museum. The first items I came across were bank notes made in the year or two prior to the 1923 Weimar Republic’s hyper-inflation crisis. It was in these small, paper notes that I realised the gravity of what I was doing. Sure, in isolation, these were just money from a defunct currency. But this money had lived. It had creases from constant folding, perhaps to put it back in the owner’s wallet. There were coffee-coloured stains from another note, perhaps from when the note was sitting too close to a cup. These weren’t just museum objects to catalogue; they became living objects with tangible connections to the past. I suddenly felt the weight of what I was doing. What I learned throughout my time cataloguing was the immense responsibility those who work in the historical sphere have to the stories they tell. Even if the actual catalogue I was working on never saw the light of day, I felt a responsibility to the lives of the objects and stories that they told.

It was halfway through my first day volunteering where I realised the most important thing, and the thing I was going to take away from my time at the museum, wasn’t the project. Sure, the cataloguing was difficult and (at times) a nerve-wracking job. It’s a daunting task, handling a Nazi war medal, let alone providing a report into its condition and historical context. But for me, the staff and their openness, patience and intelligence stuck with me. I was (rather naïvely) expecting to be treated as an outsider. After all, I was just a volunteer uni student. Instead, I was treated like a peer. The staff made sure to be inclusive and honest with me, and it made my experience all the richer.

That’s not to even talk of the work those in the Education side of the Museum do. Any question I had was met with enthusiasm, a desire to impart knowledge evident in every answer. Whilst I decry the use of war-time rhetoric in any setting, these educators really are on the front line of combatting discrimination in all of its forms. Their tireless work educating youth means having hard conversations every day, and they take this in their stride and excel at it. Those in the Education department of the museum are a credit to themselves, and to educators everywhere.

What I learned at Sydney Jewish Museum is that for everyone and everything within its walls, there is a great deal of care and empathy. They treat staff, volunteers, objects and content with care, dignity and an open mind.

Hamish Davidson, volunteered with the SJM Curatorial Department

The enigmatic character that was Adolf Eichmann has been wrestled with by many different people, from Hannah Arendt’s book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, to the recently exhibited works of Sidney Nolan in the Sydney Jewish Museum’s 2022 exhibition, Shaken to His Core: The Untold Story of Nolan’s Auschwitz which included portraits of Eichmann painted by Nolan at the time of the trial.

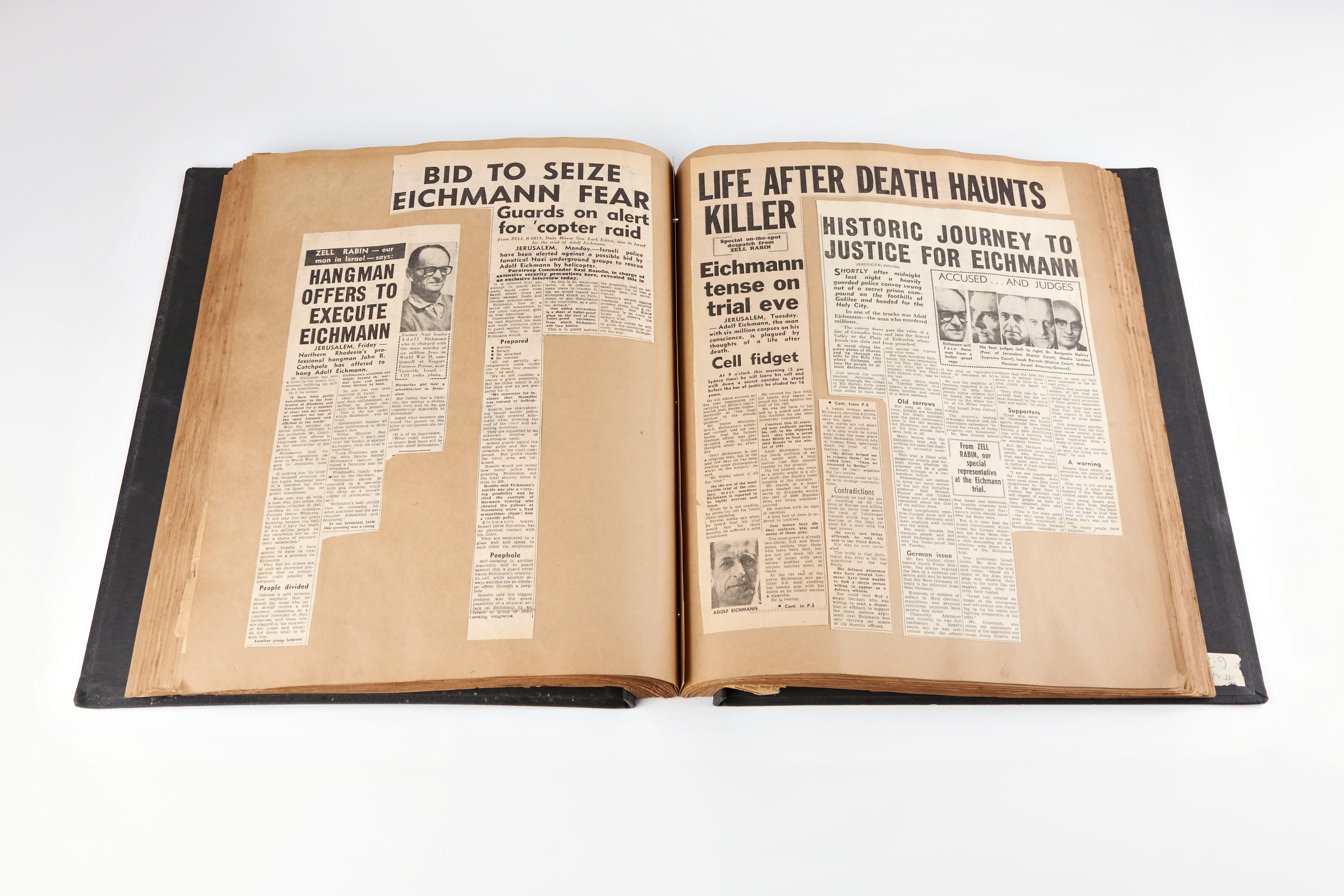

Near the very top of the Sydney Jewish Museum stands a display titled “War Crimes Trials.” In the exhibit case sits a scrapbook of newspaper clippings written by Zell Rabin, an Australian journalist who had emigrated with his family from Lithuania in 1939. The scrapbook, donated by his sister Millie Goldman, covers articles written during his time as the New York correspondent for the Australian newspaper The Daily Mirror between 1960-1961. In early 1961, Zell was sent to Jerusalem to cover the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a major architect responsible for executing the Holocaust. Zell’s voice joins the array of Eichmann commentators as a reporter struggling to understand the man on trial. He writes at the end of his time as part of the trial press corps:

“Even Eichmann says he respects the judges, but then this is not really surprising, for the man in the cage is an impossible enigma… I do not understand Adolf Eichmann and I doubt if there is anyone here who really does… He is a bureaucrat, a self-confessed coward, a sadist, a highly disciplined and indoctrinated Nazi and an organiser of such positive genius that in 1945 with Germany crumbling he could still find trains to dispatch Jews to Auschwitz.”

I had the privilege of digitally scanning, reading, and analysing this scrapbook during my time with the museum. Reading through Zell’s articles offered an opportunity to view the trial as it unfolded before his eyes. It was an experience of getting to hear his voice commentate on the nuances and peculiarities not just of the trial, but of the circumstances and context surrounding it.

Clippings from the Eichmann trial, SJM Collection

Clippings from the Eichmann trial, SJM Collection

His articles are interwoven with insight into factors such as the divided opinions on the necessity of trial and the desired outcome, the state of Israel, the proceedings of the trial, and attempts to characterise Eichmann. The enduring relevance of the Eichmann trial and the voices that provide us access to it are many. They range from the warnings they pose in the appearance of normality that evil can take when unchecked, to the call to uphold and champion justice. However, in my view the most significant impact of the trial of Adolf Eichmann and its ongoing memory is best summed up in a quote Zell takes in the days leading up to the trial. Taken from a Hungarian-born Israeli schoolteacher and survivor of the Holocaust, the significance of the trial in her eyes was not in a singular conviction, but in its enduring statement. It reads “[Whatever sentence is passed] is of no importance. What really matters is that there will be no more Adolf Eichmanns.”

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.