Blog

June 5, 2020

From Dunera to D-Day

By Emeritus Professor Konrad Kwiet

On the 76th anniversary of D-Day, we tell the story of Barney Barnett; one Jewish soldier who survived the hell of D-Day and fought against Nazi Germany until he was captured. Stories like Barney’s – of the survival of Jews fighting in Western armies and evading the Nazis’ Final Solution – have largely escaped text books.

On June 6, 1944 the Allied Liberation of Western Europe commenced. It took almost one more year before Hitler’s Empire was defeated. By then the Germans had won their war against the Jews: six million Jews had been murdered. Long prepared and code-named Operation Overlord, the invasion went down in history as D-Day.

On this day, a formidable force of more than 150,000 soldiers landed on five beaches of the Normandy coastline of France, which was heavily fortified by the monumental Atlantic Wall. 10,000 soldiers were killed. American and British troops were the first to launch the attack, quickly followed by soldiers from Canada and South Africa, France and Belgium, the Netherlands and Norway, Poland and Czechoslovakia, Greece and India, Australia and New Zealand.

By Chief Photographer’s Mate (CPHoM) Robert F. Sargent, National Archives and Records Administration, NAID 195515, Public Domain.

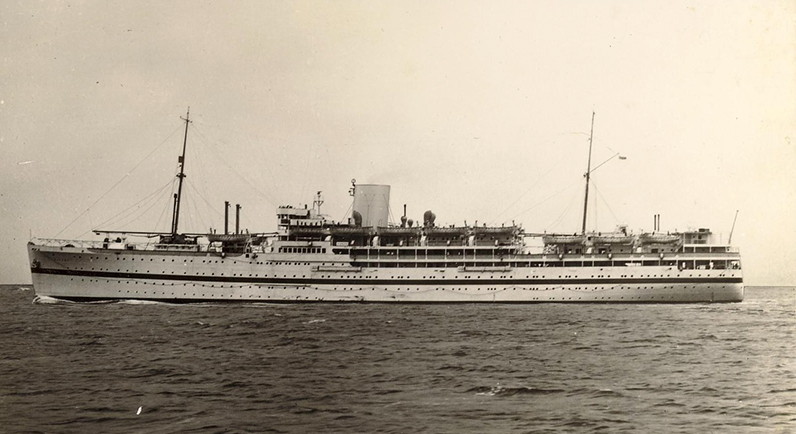

All soldiers wore a distinctive military identity tag marked with a number, and some with the letter “J” or “H” to signify their Judaism. A small group of soldiers, presumably more than 200, was made up of the legendary Dunera Boys: a group of Jewish refugees from Germany, Austria and Sudetenland who had escaped the Nazi terror prior to the war. These men found refuge in England, where they were classified as “enemy aliens” and shipped on the HMT Dunera from Liverpool to Australia. Here, they were interned in remote camps in Hay in New South Wales and Tatura in Victoria. Barney Barnett was one of these Dunera Boys.

Barney Barnett, once Horst Adolf Blumenthal, was a German Jew. Born in Berlin in 1920, he grew up in a well-off middle-class family that was, like most German Jews, firmly integrated into society as Germans and Jews. The outbreak of the great depression led to the closure of Horst’s father’s comb factory. In 1930 the family moved to Estonia where they established up a new industrial plant. Horst worked as the plant’s salesman trading in pots, pans and cutlery.

Alarmed by the news of the war and the persecution of the Jews, Horst was sent by his father to England. There he got caught in the internment of “enemy aliens”. Aged 20, Horst became one of the 1,750 Jewish refugees who was shipped on 10 July 1940 on the Dunera to Australia – together with 800 other “enemy aliens”. The dangerous voyage took 57 days and left a lasting impression on the passengers. For some it was a “Hell Ship”- for others a “Pickpocket Battleship” where suitcases and valuables were destroyed or confiscated.

Photograph of the HMT Dunera, SJM Collection.

Upon arrival in Australia, the refugees were incarcerated behind barbed wire in Hay and Tatura, guarded by friendly elderly armed Australian reservists, under the watchful eye of a Military Commandant. It was left to the new arrivals to organise camp life, which was filled with a rich program of cultural events and educational and vocational activities.

Internees were gradually released, beginning in late 1940. Of the 2,542 Dunera passengers, two thirds made the decision to leave Australia. Almost half accepted the offer to return to England or to other countries that were open to new arrivals.

Horst decided to return to England to join the British army as volunteer. On 28 November 1941 he disembarked in Liverpool after a voyage through the Panama Canal. A few days later he joined the Alien Pioneers Corps, made up of officers and soldiers from all countries of the British Commonwealth as well as from Jewish and non-Jewish exiled refugee circles.

Some 400 ex-Dunera Boys were recruited by the British army. Like many others, Horst changed his name; primarily as a measure to avoid punishment, or even execution, in the event of capture by the Germans.

Memorabilia from the Dunera Boys in the Sydney Jewish Museum’s collection

As ‘Barney Barnett’ he was first sent to work on farms and construction sites with “hayfork and pickaxe, shovel and spade”. In mid-1943 Barney’s military training started – the preparation for D-Day. Barney joined the Royal Armoured Corps. Ranked as Private he was placed into a tank unit that had just returned from North Africa, nick-named and celebrated as the “Desert Rats”.

At age 24, with the “Desert Rats”, Barney landed at Normandy Beach. His tank unit found an opening in the Atlantic Wall, through which they advanced. Barney’s tank was destroyed by a German rocket attack close to the city of Rouen. The commander was shot while attempting to escape. Barney and two comrades were taken into custody. Registered as a Jew, he was transported to Stalag VII A, located near the Bavarian village of Moosburg. Holding more than 80,000 Prisoners of War, this was one the largest German POW camps. Overcrowding and hunger, appalling sanitary conditions, harsh labour and brutal treatment determined daily life. Barney survived seven months in separate “Judenbarracken”- “Jew-Huts”.

Efforts of the Nazi SS to include Jewish Prisoners of War from Western countries in the program of the ‘Final Solution’ had failed. The German army, concerned about the treatment of German soldiers and civilians interned abroad, refused to hand them over to the SS. However, the Germany military was not concerned about the murder of Jewish and non-Jewish Soviets POWs: over 3 million were starved to death, shot or killed in gas chambers. American soldiers liberated Barney on 29 April 1945. Only then he learned that the Germans had murdered 6 million Jews, including members of his extended family.

Barney returned to England to offer, like other Dunera Boys, his services to a British Intelligence units. He translated Nazi documents that were to be used in the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg.

In 1947 Barney was discharged from the British army. At the same time, he had applied for and was granted British citizenship; this was a cause for joy and gratitude. Together with a young wife, he returned to Australia to rebuild his life.

Barney’s experiences and skills, hard work and endurance paid off. First trading in pans and buttons, then in belts and zippers, finally in knitwear and haberdashery, he established a successful and lucrative family business in Sydney. By this time Barney had become a proud Australian citizen. Together with his wife and daughter, he embraced the communal life of his synagogue and enjoyed the regular reunions of the Dunera Boys where I met him in 1976. Years later – in 2011 – my wife and I recorded his survival story which was published in German.

Barney died in 2004, aged 90. He was buried on the Jewish section of the cemetery in Surfers Paradise in Queensland. Barney’s home in Robina was full of memorabilia documenting his turbulent life and, in particular, his career as a British soldier landing on D-day in Normandy and fighting the Germans.

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.