Blog

April 22, 2020

Out of Egypt

Every year, Jews all over the world sit around their Passover table and listen to the youngest member of their family asking the perennial question: Why is this night different from every other night? The short answer is “because we were once slaves to the Pharaoh in Egypt and now, we are free”. Then follows the telling of the miraculous story of the ancient Jews’ hasty exodus from Egypt through the reading of the Haggadah. However, this is not meant to be just story telling. Parents are supposed to explain the significance of the ritual in a way that is accessible to each one of their children, based on his or her ability to comprehend. It can be achieved in a variety of ways and should include all the Seder participants, such as dramatising the Passover story through re-enactment, dressing up, communal singing, and on a more serious note, drawing comparison between that ancient exodus and similar current events such as the plight of refugees.

For the Jews of Egypt in the mid-twentieth century, this was not just a mythical story. This was their story. As a Sephardi Jewish girl born in Alexandria, Egypt in 1939, this was also my story. My childhood was carefree and happy. The Mediterranean was my playground. My siblings and I went to a French private school. The Jewish community lived freely in a cosmopolitan and tolerant society together with other ethnic minorities. We all spoke a variety of languages, but everybody used French as the lingua franca. At home, we led a very Jewish life, celebrating openly all the festivals and attending synagogue regularly.

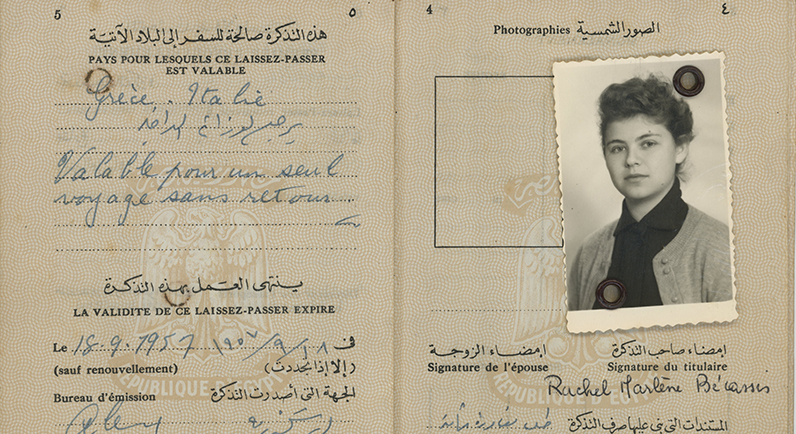

Nevertheless, the end of that golden age was in sight. The creation of the state of Israel in 1948, the subsequent Egyptian-Israeli conflict in 1956 and the 1967 Six-Day War sealed the fate of my community. Under Egypt’s President Nasser, “the Pharaoh who did not know Joseph”, Jews were either expelled or harassed into leaving and abandoning all their possessions. Their travelling papers were stamped with a one-way exit visa that specified they could never return or claim any compensation. The majority settled in Israel and the rest dispersed all over the western world. Today, all that is left in Egypt of that vibrant Jewish community is literally a handful of ageing women between Cairo and Alexandria, haunting the corridors of our beautiful but empty synagogues.

Egyptian passport belonging to Racheline Abécassis, Alexandria, 19 March 1957. It is only valid for one trip and states she is not allowed to return.

My connection with Egypt is particularly strong at Passover, when I hear the last words of the Haggadah: “In every generation it is our duty to regard ourselves as though we personally have come out of Egypt”. Like other Jews from Egypt, I don’t have to pretend. We literally did come “out of Egypt” in great haste and we did not have time to wait for our bread to rise.

Back in Egypt, I remember clearly the feverish atmosphere in the weeks preceding Passover. Our household was tipsy-turvy. My mother and my grandmother worked tirelessly to have everything ready before the start of the festival. All the rooms of our home had to be freshly painted. We had a dedicated room for the preparation and storing of the Passover foods.

I remember the aroma of the nuts and the spices being freshly roasted. I remember the pickling of vegetables, olives, lemons, and tiny eggplants. I remember the mountain of rice that needed to be cleaned. Contrary to Ashkenazi tradition, rice, being the staple food of Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews, is allowed over Passover. It was customary in Egypt to check the rice three times to ensure there were no kernels of chametz.

The symbolism of the Seder plate is basically the same in both the Sephardi and the Ashkenazi worlds with a few variations. Egyptian Jews make their harosset with dates, readily available in the Mediterranean, instead of apples. The eggs served at the end of the Seder are boiled for hours with brown onion skins, giving them the appearance of being roasted. The main meal consists of a shoulder of lamb and potatoes. Another common fixture at the Egyptian Seder table as a symbol of spring and renewal is a matzo dish called mina or mayeena, made with leek or spinach.

Apart from the food, there were some uniquely Sephardi traditions in the running of the Seder. For instance, during the reading of Dayenu, we used to pass the Seder plate around the table, tapping it on the head of each participant, to remind us how much God did for us when we went out of Egypt.

I also remember going around the Seder table carrying a small bag on my shoulders and everybody would ask me “where are you coming from?” I would say “from Mitzrayim” (Egypt), followed by: “and where are you going?” to which I would answer “to Yerushalayim” (Jerusalem).

Racheline’s wedding day in Rome, Italy, 1957.

It is clear that although I have been “Out of Egypt” since 1957, my memories of Egypt have not left me. I can never forget my childhood in Alexandria and the happy and easy life we led, together with my parents, my siblings and extended family. I can never forget that Alexandria is where I met my future husband just before our “second exodus” from Egypt. Our marriage in Rome a few months later was the only bright light at a time when his family was totally distraught, having lost everything and I was separated from my own family. And finally, I can never forget my first Seder as a married woman. It was on Monday the 15th April 1957, one day after our wedding at the Great Synagogue of Rome.

For more information about our upcoming exhibition, Jews from Islamic Lands, click here.

Author: Dr Racheline Barda

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.