Blog

December 19, 2019

Auschwitz: The exchange of belongings

By Emeritus Professor Konrad Kwiet, Resident Historian

Auntie Leida, a distant relative of mine in Holland, once told me that she had taken her wedding dress to Auschwitz. She never saw it again. So many Jewish people deported to camps brought their most valuable and sentimental possessions with them to the camps. Where did they believe they were going, and what became of their precious belongings?

Jews called up for deportation were given clear instructions regarding luggage by the SS. But they were given little time to select what to take with them on the harrowing journey to the murder sites. The train journeys they boarded were disguised as “labour deployment” or “resettlement in the east”. The provision of luggage let these people hold onto a sense that they were still connected to their old world, and that there was a promise of life at their destination.

Three travel bags were permitted for each person: a suitcase, a piece of hand luggage and a rucksack, which together could not exceed 50 kilograms. People filled their allowances with clothing, bedding, crockery and footwear – often the finest pairs of Bata shoes – personal documents, including passports, identity cards, certificated, family photos and letters. Permission was given to take some medication and cleaning materials. The medication included tablets and ointments, cough mixtures and cod liver oil, band-aids and bandages. Other essential items were toiletries, sewing kits and, of course, food for the journey. Females found a place for their cosmetic and hygienic items, including sanitary napkins; males were anxious to pack their shaving kits. Children chose one or two of their favourite belongings – a teddy bear or doll, a book or diary. Strictly observant Jews could not abandon their religious artefacts: their kippah (male head covering) and scheitel (female wig), tallit (prayer shawl) and tefillin (a set of small leather boxes containing verses from the Torah) as well as prayer books, kiddush cups and candle sticks.

Precious objects such as jewellery and money were strictly forbidden. Prior to deportation Jews had already been robbed of most of their belongings. Once deportees crossed state borders, all property left behind was stolen by the Nazi State. Some Jews, however, managed to hide coins, bank notes and valuables in their travel bags – to no avail.

Upon arrival at the railway platform, the luggage was confiscated. It was brought by trucks or wheelbarrows to a near-by site, nicknamed “Kanada” – a place of “wealth”. Workers hastily sorted through the belongings. The best pieces were sent to Germany, and less valuable items ended up in two other camp depositories: the Bekleidungskammer (the clothing storehouse) and the Schuhkammer (which stored piles of shoes). “Kanada” also provided goods for the flourishing black market.

New arrivals who were selected at the arrival platform for murder were lined up and driven to the gas chambers. After entering the adjacent undressing room, their clothes, glasses, watches and artificial limbs were all taken. A group of workers, made up of dentists and dental technicians, searched for and removed gold fillings and other valuables. The metal was melted into ingots and sent to Berlin to be deposited in the safes of the German Reichsbank.

Jews selected for work experienced the humiliating and painful rituals of registration, which took place in a building disguised as a “sauna”. Clothes, shoes and any other belongings which they still carried with them were taken away. Showering and the cutting of hair followed. They received new clothes; initially tattered and contaminated military uniforms from murdered Soviet prisoners of war. Once the Russian uniforms ran out and the demand for camp garments increased, civilian clothes were distributed. They came from the stores of clothes and shoes confiscated upon arrival. The prisoner uniform of men included a cap, shirt, trousers and jacket and one set of underwear. Women’s clothes included a head scarf, blouse, skirt and underwear, but no bra. Prisoners were also forced to accept replacement shoes, often ill-fitting and mis-matching. In addition to their allotment of redistributed clothing, prisoners were then tattooed on their arm with their prisoner number, which was also attached to outside of their uniform.

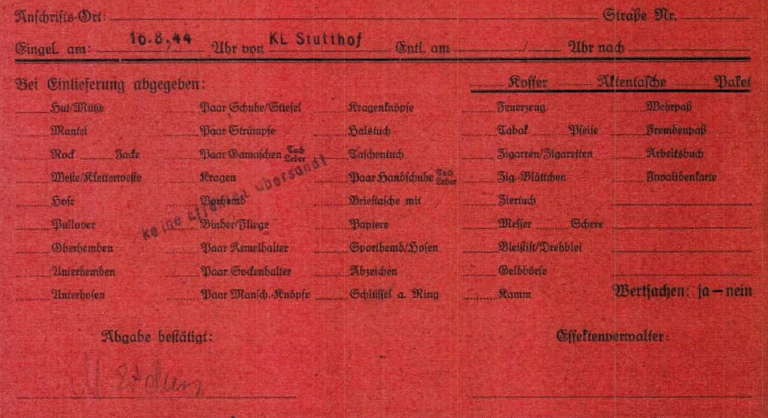

When prisoners arrived in other camps from the Death Marches from Auschwitz in early 1945, they were registered again. They had to sign a card that recorded their personal belongings. However, none of the boxes were ever ticked. Instead, the centre of the card was stamped confirming “Keine Effekten überführt” – “No belongings recorded”.

Wherever survivors were liberated – in overcrowded concentration camps or factories, on roads or along railway tracks, in forests or in barns, they possessed no papers or documents, let alone hand luggage. They were exhausted and confused, overwhelmingly young and single, marked by traumatic experiences, wounds which never healed.

Aunty Leida also told me that, upon liberation, she still had two markings that had been imposed upon her and which left an indelible mark on her memory and identity – the yellow Jewish star and the dark blue Auschwitz tattoo. In the wake of German restitution payments, she received later five Deutsch Mark for each day that she was forced to wear these marks of the Holocaust.

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.