Blog

June 10, 2016

Learning to let go

In the countdown to the exhibition opening there are lots of little deadlines. Today I feel like a huge weight has been lifted as we are getting close to signing off final proof of the maps. The maps have given us all sleepless nights. International borders shift continuously. Names of places change. As Anna Berger, one of our Curatorial Committee members would say, it is possible to have been born in Austria-Hungary, married in Czechoslovakia, have given birth in Hungary and resided in the Ukraine, and never have left the city of Munkacs. Or should that be spelled Munkacheve?

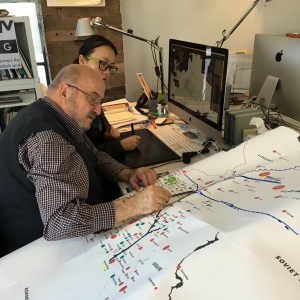

I went with our resident historian, Professor Konrad Kwiet, to the designers studio this afternoon to make some amendments to the maps and I don’t know if I’m more impressed with the graphic designers skills in creating these maps from scratch or our historians extraordinary knowledge of geography.

Around 1,200 ghettos were established during World War II to isolate, concentrate and control the Jews. One of the maps illustrates 230 of the ghettos, most of them established in occupied Poland. In this photo, I’ve captured the moment of Konrad hand-drawing the borders between the Ukraine and Belarus and noting that Starokostiantyniv should actually be located a little further to the left, and Zhmerinka a little to the right. Then we move on to the Einsatzgruppen map and I watch as Konrad corrects the routes of the SS-Einsatzgruppen and Police Battalions.

PHOTO PROF KONRAD KWIET WITH THE DESIGNER HAIMENG ZHAO FROM X SQUARED DESIGN

As the designers refine the showcase designs I’m discovering that I have to let go of emotional attachments to certain objects that simply don’t fit in.

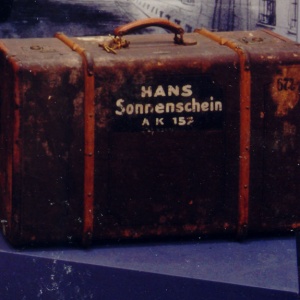

One of the items is a suitcase carried by Hans Sonnenschein when he was deported from Prague to Theresienstadt.

Deportees were allowed to bring one suitcase of possessions weighing no more than 50kg. Suitcases were marked with their names and transport numbers. In October 1944 Hans was deported to Auschwitz and murdered. Prior to his deportation he had handed over his suitcase to his brother who survived Theresienstadt. After the war the brother went back to Prague. He gave the suitcase to his nephew to use when he immigrated to Australia in 1947. That is how it found its way to our collection.

A suitcase is probably the most iconic object or context marker of immigration. It is an archetypal symbol of displacement and movement. The container and its contents, however meagre, are precious possessions carried to a new life. Sadly the original owner, whose name is clearly written in white paint together with his transport number, never had the opportunity to carry it to a new life.

Author: Roslyn Sugarman, Curator.

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.