Blog

May 8, 2020

Jewish Doctors – Combatting Diseases During the Holocaust

By Emeritus Professor Konrad Kwiet and Dr George Weisz

Ghettos, concentration camps and forest hideouts were distinct locations where Jewish doctors continued to care for the sick, the injured and the dying during the Holocaust. Throughout Hitler’s Europe, their medical accreditation had been cancelled, banning them from treating non-Jewish patients.

As long as and wherever Jews were allowed to live, Jewish doctors were indispensable. They also had a slightly higher chance of survival than other professionals. When in 1941, for example, the mobile killing units of the SS and local police committed the first wave of mass executions in Eastern Europe, some doctors were spared.

They were also required to perform their duties in ghettos and camps. Some managed to escape from ghettos, deportation trains and camps, finding their way to the partisans in the forests.

In Eastern Europe they were not always accepted; doctors and nurses, however, had a good chance of being admitted. In 1936 some 3,000 Jewish physicians were registered in Poland. 10 percent survived.

Jewish doctors in Auschwitz survived nearly 10 times inmates selected for labouring work. Within the strict hierarchy of the camp, they acquired the status of ‘prominent’ and ‘privileged’ prisoners – treated less brutally, receiving more food and cleaner clothing, working and sleeping in separate, more ‘sanitised’ places. Furthermore, they knew how to protect themselves from infectious diseases and, equally importantly, they were distinguished by a strong will to live.

The historian Ross Halpin argues: “The story of their survival is one of courage, sacrifice and inspiration. In a sea of evil, it is a story in which the doctors continued to keep their dignity and displayed humanity to their fellow human beings, whether Jews or non-Jews”. And yet, all survivors had one thing in common: they survived by sheer luck, or, as one survivor has expressed it, by an “accident by fate”.

Ghetto inmates lived on borrowed time. Incarcerated behind walls or fences, they were subjected to terror and slave labour, appalling accommodation and unhygienic conditions, rampant starvation and spiralling disease. Tens of thousands perished. Inmates did their best to resist and sustain themselves physically and spiritually. Doctors and nurses cared for patients in sick bays or hospitals lacking medical supplies. When the Warsaw ghetto was sealed off – squeezing 460,000 Jews into a tiny area of 3.4 square kilometres with an average 9.2 people per room – the number of hospitals totalled 16. After the ghetto uprising in spring of 1943, all buildings were razed, and some 57,000 Jews were deported to extermination camps.

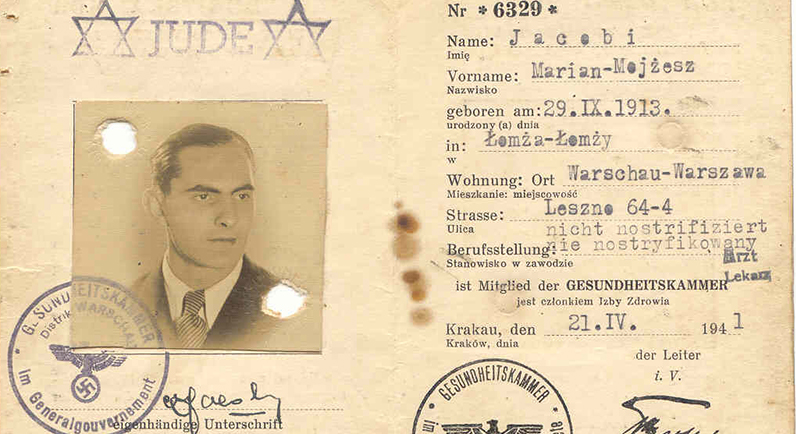

Identification card belonging to Dr Marian-Mojzesz Jacobi, who was a doctor at a hospital for infectious disease in Warsaw. SJM Collection.

In Warsaw, and in some other large ghettos, pioneering medical research was conducted to find life-saving cures for diseases and epidemics. Doctors studied the ‘famine disease’, tested all organ systems, recorded the findings and buried the findings in metal containers. The contents were recovered after the war and published the starvation-related diseases textbook, praised for its exceptional scientific value.

The findings included the warning to survivors, once liberated, not to over-eat. They explained that, a rapidly recovering metabolism would put excessive load on the heart. This prediction tragically became reality when thousands died in the immediate aftermath of liberation from camps such as Bergen Belsen.

Apart from their clinical work, the doctors in Warsaw attracted some 40 medical students. With 27 teachers, of whom 16 survived, they established a clandestine medical school.

The Germans, when establishing ghettos and camps, were extremely fearful of epidemics, which breached walls and fences, threatening the health and life of non-Jews. An army of Nazi doctors therefore selected Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners as guinea pigs for their barbaric ‘medical’ experiments. High priority was given to infectious diseases such as hepatitis and tuberculosis, diphtheria, dysentery, typhus and typhoid fever.

Jewish physicians, bacteriologists and immunologists were recruited to develop a vaccine against typhoid fever, a highly infectious disease transmitted by lice. In 1942, it ravaged not only the starving ghetto population with their lowered immunity but also the German soldiers at the Eastern front.

Dr Helmut Vetter, an infamous Auschwitz Nazi doctor, supervised the experiments. He recruited Dr Ludwik Fleck, a renowned Jewish physician and biologist studying the typhus epidemic in the Lwów ghetto. Fleck was brought to Auschwitz and then to the Institute of Hygiene within Buchenwald. He and his team of Jewish doctors developed a vaccine, hailed as a success by Helmut Vetter. However, Fleck sabotaged the success. Two batches of vaccine were developed: a fake batch was given to German soldiers and the effective vaccine to Jewish inmates. The fake remained undiscovered until after the war.

Vetter was hanged in the Landsberg prison. Fleck survived with his family. His life ended with a heart attack while working in Israel’s biological laboratories.

Equally important Dr. Jakub Penson’s research in Warsaw. He studied acute kidney failure during the typhus epidemic, discovering how to prevent, diagnose and treat it. After the war, admitted to the Polish Academy of Science, he published his pioneering Holocaust research.

Some 31,000 Holocaust survivors re-built their shattered lives in Australia. Among them were several doctors who had attempted to save the lives of their Holocaust patients.

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.