Blog

December 17, 2020

International Migrants Day: Waves of Jewish migration to Australia

The waves of Jewish migration to Australia before and after World War II have been turning points in the history of Australia’s Jewish culture and community. Each group that has arrived has altered the community’s demographic make-up, its institutions and religious practices. These arrivals have also been milestones on Australia’s path to emerging as a multicultural society.

The arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 signaled the beginning of European settlement in Australia. It also paved the way for Jewish people to settle at the edge of the diaspora.

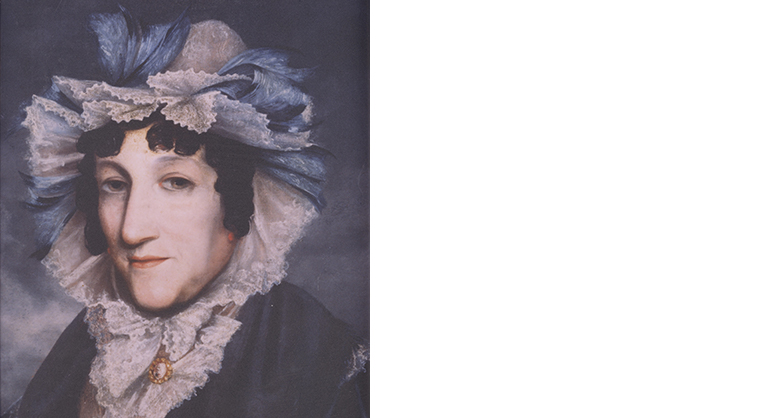

Reproduction of a portrait of Esther Abrahams, a Jewish woman from London sent to Australia as a convict on the First Fleet.

However, colonialism and racism also made way for the brutal treatment of Australia’s indigenous population. Aboriginal people were degraded to slaves, robbed of their children, land and cultures, massacred, and some regions were totally wiped out through genocidal campaigns.

Since the 18th century, Jews arrived in Australia in stages.

Australia was never a ‘free’ or ‘open’ country of migration, and rigid quotas and selection criteria determined the intake of migrants. However, there was an unwritten directive that the intake of Jews was to be in line with general population growth. Until today, Jews represent no more than 0.5 percent of the overall population of Australia.

800 of the 151,000 convicts shipped to Australia after 1788 were Jewish. Most of them came from London. They were members of poor, lower classes who had been punished for minor offences.

In the 1830s the free settlers arrived. Among them were Jewish people who established small congregations and synagogues in Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart and Launceston, later in Adelaide and other places, including a few rural areas. The rhythms and rites of Jewish life were based on those of Anglo-Saxon Jews, fusing Jewish tradition and British culture. This tie to British Jewry prevailed in Australia until World War II.

Recreation of George Street in the 1840s showing the many Jewish businesses.

At the end of the 19th century some 6,000 Jews were living in Australia. Another distinct Jewish group arrived: refugees from Eastern Europe who were escaping poverty, persecution and pogroms. About 3,000 Jews from Poland and Russia had found refuge in Australia by 1923. They had to prove they had family connection in Australia. They also required professional qualifications considerable funds at their disposal to be able to afford the expensive travel and entry costs.

In 1933 the National Socialists seized power in Germany, proclaiming to solve the ‘Jewish Problem’ once and for all. By then 23,000 Jews were residing in Australia.

Escaping Nazi terror, some 9,000 Jews from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia managed to obtain life-saving landing permits and travel documents. Thousands of application forms were still being processed when the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 ruled out all possibility of emigration.

Initially, the German-speaking refugees encountered huge difficulties in gaining a foothold in their new and alien environment. Upon arrival they were regarded as foreigners, as Germans, as refugees and as Jews; colloquially known as “reffos”, “bloody reffos” or “refew-Jews”. They occasionally felt the brunt of xenophobic sentiments or were subjected to antisemitic attacks. After the outbreak of the war they were classified as ‘enemy aliens’ and subjected to restrictions ranging from the confiscation of binoculars to postal censorship and the restriction of movement.

Other ‘enemy aliens’ were sent from England and other parts of British Commonwealth to Australia. The largest group arrived in 1940. It comprised more than 2,500 men, including 1,780 Jews, refugees from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia. Over 800 of them stayed in Australia. They applied for Australian citizenship and accepted their certificates with joy and gratitude. In time, these migrants integrated into the life and culture of their adopted country.

Photograph of European Jewish migrants arriving aboard the SS Derna, 6 November 1948. Photo taken by The Age newspaper, Melbourne.

The first Holocaust survivors came to Australia from the Displaced Person Camps set up in Germany, Austria and Italy. Other survivors followed soon after; they had been labelled as ‘unwanted’ or they were unwilling to live in their destroyed communities under Communist rule in Eastern Europe. Altogether more 31,000 Holocaust survivors rebuilt their shattered lives in Australia. In proportional terms, Australia welcomed one of the largest numbers of Holocaust victims.

Photograph of Olga and John Horak at their naturalisation ceremony at the Bondi Beach Pavilion in 1954. Olga and John are on the far right hand side. They had arrived in Australia as refugees on 16 September 1949. SJM Collection.

In subsequent years, the exodus to Australia continued. 2,000 Jewish people who had survived the Holocaust in China’s cities of Harbin and Shanghai arrived. 2,000 Sephardic Jews, expelled from their homelands in North Africa, Egypt and other Arab countries, found a new home in Australia. Between 14,000 and 15,000 Jews turned their backs on the apartheid system in South Africa. Around 10,000 Jews came from Russia. More than 7,000 left the state of Israel for Australian shores.

Today Australia is home to about 120,000 Jews. Holocaust survivors and migrants have played a vital role in establishing a diverse and vibrant Jewish community which has found a safe place at the edge of the diaspora.

Author: Emeritus Professor Konrad Kwiet, Resident Historian

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.