Blog

August 28, 2024

Revisiting the 1959–1960 Swastika Epidemic: a forgotten chapter in Australia’s history

By Dovi Seldowitz

In December 1959, a pair of vandals in Cologne targeted the local synagogue and Holocaust memorial with swastikas, sparking a wave of similar incidents across West Germany and other countries in Europe. Within weeks, the wave of swastikas and antisemitic graffiti that defaced buildings across Europe spread to the United States, Canada, South America, South Africa, Hong Kong, and Australia. This surge in hate crimes was soon dubbed a ‘swastika epidemic’ shocking Jewish communities, and stirring a profound sense of alarm. In Australia, an estimated 20–30 incidents took place in January and February, but news of these events was overshadowed by the hundreds of incidents taking place in other countries.

Notedly, the disease metaphor and imagery appear while the event was unfolding. A Daily Mail cartoon at the time, and republished in The Bulletin on Jan 20, 1960, depicts a hospital scene where a bedridden man (representing Germany) is covered in small swastikas. The infected patient is surrounded by political leaders dressed as a team of doctors. Wheeling in his patient, German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer dressed as a doctor announces, ‘measles again,’ while his colleagues, French President Charles de Gaulle, British PM Harold Macmillan, US President Dwight Eisenhower, and Israeli PM David Ben-Gurion look on in concern.

Figure 1: Daily Mail cartoon republished in The Bulletin (Jan 20, 1960).

Figure 1: Daily Mail cartoon republished in The Bulletin (Jan 20, 1960).

Tracing the contagion

The catalyst for the 1959–1960 antisemitism pandemic was the Christmas Eve desecration of the Roonstrasse Synagogue in Cologne by two members of the far-right Deutsche Reichspartei (DRP). The painting of swastikas and antisemitic slogans on the synagogue walls was, unfortunately, not a unique event in West Germany. Similar attacks had taken place in the two years preceding the event. Expectedly, this act shocked the local Jewish community and garnered the condemnation from German chancellor Konrad Adenauer. But unlike the previous events, the stirrings of hate were quickly manifest around the world, and in turn, Jewish communities responded with mass demonstrations. By late January 1960, a series of incidents took place around Australia, prompting sharp responses from civic and religious leaders who were shocked to find the memory and lessons of the Holocaust would need to be activated with force.

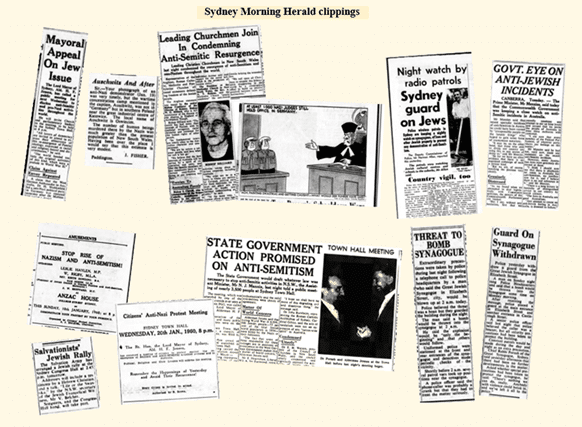

Figure 2: A selection of clippings from the Sydney Morning Herald (January 1960)

While a complete list of incidents occurring in Australia was never published, a search through the digitised collection of Australian newspapers reveals the national spread of the pandemic and the different sites targeted with hate. In this assessment, Jewish sites should be viewed as primary places where incidents occurred. While other sites are only targeted in a spillover effect. In Melbourne, a rock thrown through the windows of Temple Beth Israel, and swastikas painted on the Zionist Federation building. In Sydney, The Great Synagogue received bomb threats. In Canberra, swastikas on a Jewish-owned bakery. Buildings not associated with Jews and Judaism also served as means to direct hate at the Jewish population with swastikas painted on a Motor Registration building and a Catholic school building in Melbourne, on a police building in Perth, and on a Church building in Western Sydney. Likewise, regional areas were not entirely immune. Swastikas appeared on an R.S.L. building in Whyalla, South Australia, and on the Town Hall building in Maryborough, Queensland. Other swastika and antisemitic slogans appeared in nonspecific areas, such as in public parks and on or near residential homes. One does not have to be Jewish to be affected by antisemitism.

Figure 3: Clippings from The Canberra Times (Jan 7-9, 1960).

Figure 4: Clippings from the Australian Jewish News (Jan 8 and 20, 1960).

“Not in our society”

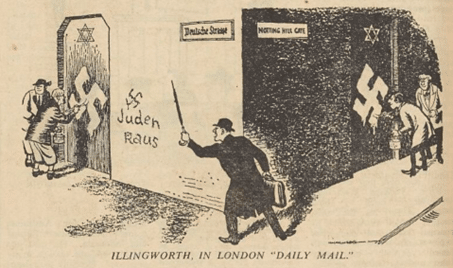

The widespread use of the swastika outside of Germany likely befuddled many observers who could not fathom Nazism in their own backyard. In their mind, antisemitism was a German problem and could not possibly be an Australian one. This sentiment is similarly captured in a Daily Mail cartoon republished in The Bulletin (27 January 1960) which depicts a sharply dressed Londoner shouting at a pair of men painting a swastika on a German synagogue while in the shadows a similar pair of men are painting a swastika on a British synagogue. With increasing evidence that no country was immune to antisemitism a sense of dissonance would have to be produced. A self-congratulatory editorial in the Sydney Morning Herald (22 January 1960) proclaimed that ‘Sydney, fortunately, has been almost free of the overt acts of anti-Semitism…’ That this statement was made after reports of swastikas painted on churches bomb threats being made against The Great Synagogue is not incomprehensible. Perhaps with their collective reputation on the line, it was important for the newspaper editors to present Sydney as a place without a real problem to confront.

Figure 5: Daily Mail cartoon republished in The Bulletin (Jan 27, 1960).

Civic and Religious Responses

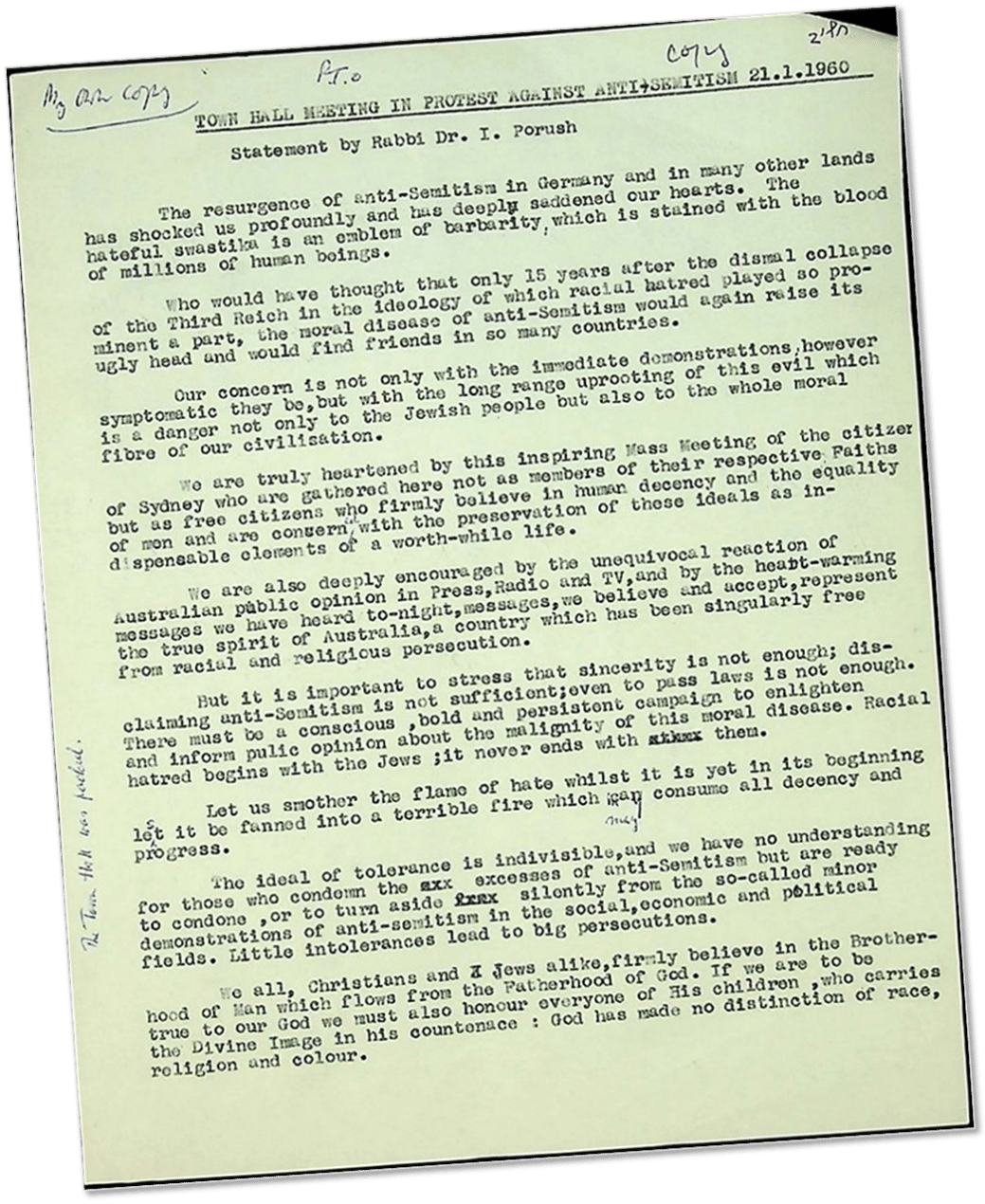

Members of the Jewish community in Australia organised several public meetings to protest the sudden rise in antisemitism. The typewritten statement delivered by Rabbi Dr Israel Porush at a 21 January 1960 event at Sydney’s Town Hall is preserved in the Australian Jewish Historical Society archives. A small note on the margin in the rabbi’s handwriting reads ‘The Town Hall was packed’, and the reporting from time stated that 2,400 people filled the main Town Hall, and additional 1,000 people filled the lower hall. Welcoming the robust response from many non-Jewish leaders who condemned the recent events, the rabbi stated, ‘it is important to stress that sincerity is not enough; disclaiming anti-Semitism is not sufficient; even to pass laws is not enough. There must be a conscious, bold and persistent campaign to enlighten and inform public opinion about the malignity of this moral disease. Racial hatred begins with the Jew; it never ends with them.’ Rabbi Porush also criticised those in Australian society who sought to downplay the lesser manifestations of antisemitism, stating ‘the idea of tolerance is indivisible, and we have no understanding for those who condemn the excesses of anti-Semitism but are ready to condone, or to turn aside silently from the so-called minor demonstrations of anti-Semitism in the social, economic, and political fields. Little intolerances lead to big persecutions.’

Figure 6: Copy of Rabbi Porush’s statement at the protest against antisemitism (Australian Jewish Historical Society archives, Box 5, Folder 33)

The Prime Minister weighs in

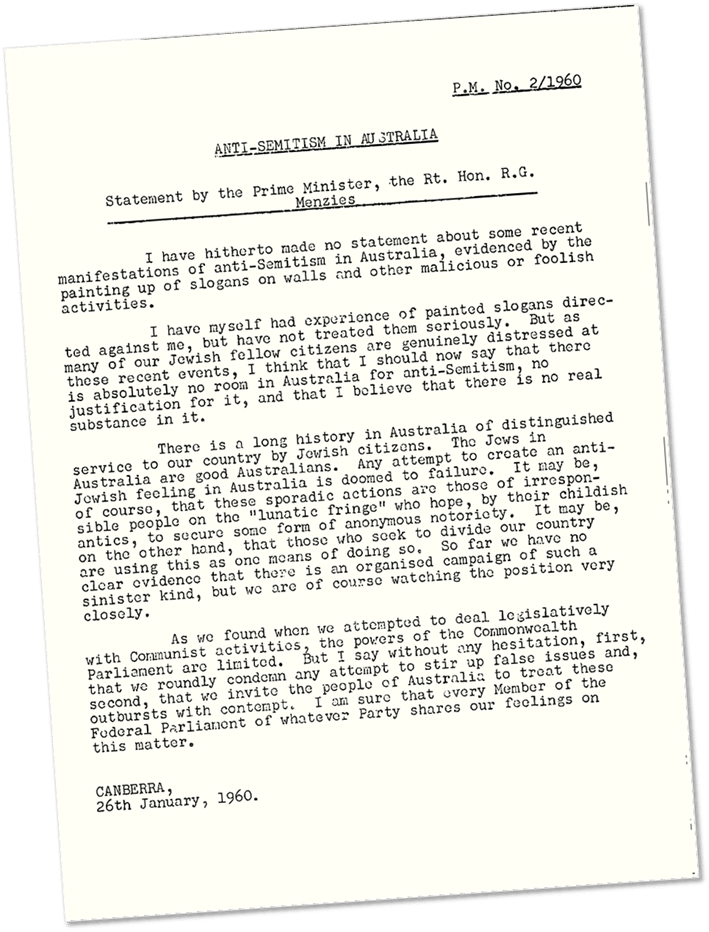

Five days later, the Australian Prime Minister produced a statement that begrudgingly acknowledged that antisemitic activity had occurred in the country, characterising it as a problem for the Jewish community. He stated, ‘I have hitherto made no statement about some recent manifestations of anti-Semitism in Australia, evidenced by the painting up of slogans on walls and other malicious or foolish activities. I have myself had experience of painted slogans directed against me, but have not treated them seriously. But as many of our Jewish fellow citizens are genuinely distressed at these recent events, I think that I should now say that there is absolutely no room in Australia for anti-Semitism, no justification for it, and that I believe that there is no real substance in it.’ Menzies went on to list the ways in which Jews have been good Australian citizens, the practical limitations on government intervention, and the need for political parties to condemn such acts. While Menzies’ message clearly expressed that harm to Jews was unacceptable in Australia, the implicit minimisation of Jewish suffering remains problematic. The rapid public appearance of symbols and acts associated with a movement that systematically killed six million Jews was presented as merely the work of hooligans, no different from the mischievous vandalism that might be directed at a political figure.

Figure 7: “Anti-Semitism in Australia”, statement by Prime Minister Robert Menzies (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet)

Ripple effects

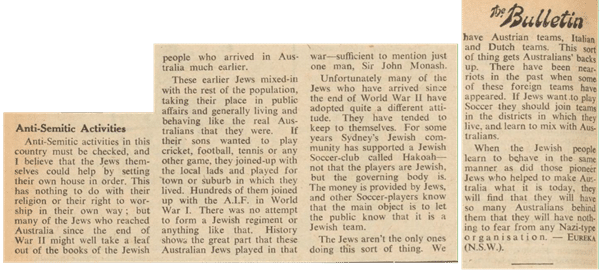

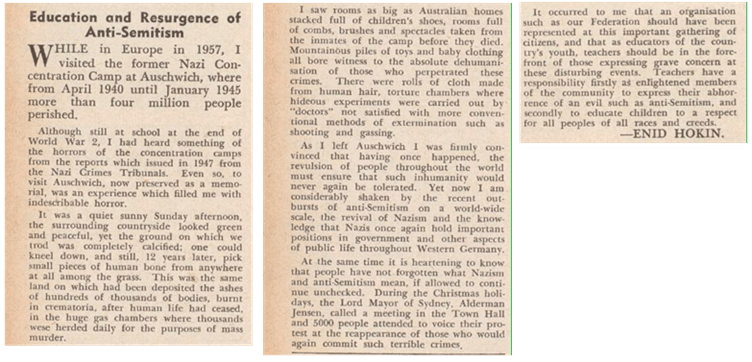

The episode sent ripples through Australian society. In some instances, it encouraged other forms of antisemitic sentiment, such as a letter to The Bulletin, published on 10 February 1960, which called on Jews to stop standing out as a distinct group and to assimilate into the Australian public. In other cases, the events – particularly the community response – had a positive effect on bystanders, such as one teacher who, in a letter to Education, the journal of the New South Wales Teachers’ Federation, published 23 March 1960, shared her previous visit to Auschwitz and raised the need for teachers to take an active role in educating children about the dangers of hate and the need to respect people of different faiths and heritage. In many ways, the various dynamics present in this forgotten chapter of Australian Jewish history – overt forms of hate, a bias of omission, increased sentiment in support and opposition of Australian Jews – are found again in more recent episodes of Australian antisemitism.

Figure 8: Letter published in The Bulletin (10 February 1960).

Figure 9: Letter published in Education: Journal of the NSW Teachers’ Federation (23 March 1960).

About the author

Dovi Seldowitz is a PhD student (Sociology) at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. Previously, Dovi directed and curated the 2022 B’nai B’rith Kabbalah Exhibition and was the recipient of the UNSW University Medal in Sociology and Anthropology for his Honours thesis on Hasidic women’s leadership. In 2024, Dovi was the SJM Lotte Weiss Memorial Visiting Scholar and researched the religious activism of Rabbi Dr Israel Porush and his efforts to combat antisemitism in Australia.

What’s On Newsletter

Keep up to date on all Museum events and exhibitions.